Here is the result in plain text:

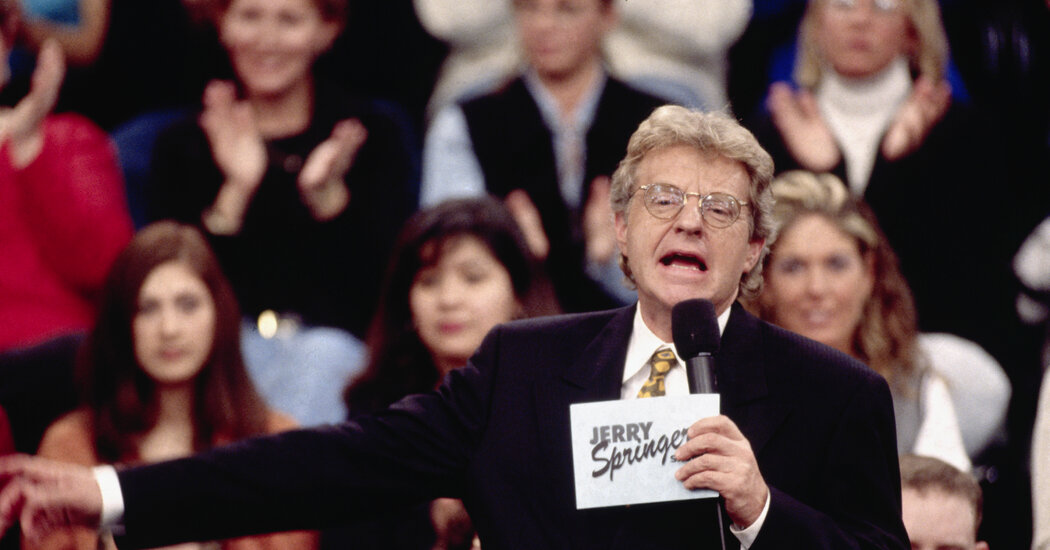

Ask people why American culture is going down the tubes, and the culprits might be partisanship, declining trust in institutions, empty calorie entertainment. Or maybe the answer is an episode of “The Jerry Springer Show” from October 1997. That’s when “Springer,” a daytime talk show that reached around eight million daily viewers at its peak, aired “Klanfrontation!,” an episode in which a chaotic brawl broke out among Klansmen, a Jewish activist and audience members.

Nothing quite like those fisticuffs had been seen on television, and the episode drew heavy criticism. But it also drew eyeballs, which, as the two-part Netflix documentary “Jerry Springer: Fights, Camera Action” makes plain, was the point. “If you’re producing a show that you want to be insane and unlike anything that’s ever been on TV before, there’s your goal,” the show’s cutthroat executive producer, Richard Dominick, says in the documentary, referring to “Klanfrontation!” Once that episode aired, he “never tried to do anything that didn’t fall into some kind of confrontation.”

In a world where slugfests on “Real Housewives” are ho-hum, and where a felon and former reality star is the president-elect, it’s hard to imagine that such scenes were ever noteworthy, let alone shocking. But as the British director of “Fights, Camera Action,” Luke Sewell, argues, the episode was a turning point for “Springer,” which went on to have a coarsening effect on American culture that has only worsened since. “I think that it obviously led to quite a dark place,” Sewer said in a recent video call. As the show leaned on hand-to-hand combat and outré sex topics (“Diaper Bob” was a fan favorite), it “pushed the envelope in ways that no one else had,” and gave permission for everyone that followed them to go there.

Springer had a way of getting people on his side. In 1991, Springer hosted a serious but unremarkable talk show in Cincinnati, where he was once mayor. He was a shrewd communicator, a skill that helped him navigate the various controversies the show generated after it moved to Chicago and became a circus, particularly after Dominick, a former tabloid journalist, took over as the show’s executive producer in 1994.

The show and Springer were sued unsuccessfully in 2002 by the family of Nancy Campbell, a woman who was killed by Ralf Panitz, her ex-husband. Both, along with Panitz’s more recent wife, had been guests on the show. The killing happened on the day the episode aired nationally. “What is interesting about the murder is that it showed how out of control things had gotten” in the making of “Springer,” Sewell said, adding: “It raised all sorts of questions about duty of care.”

The producers played with fire. Sewell said he had been stunned at the producers’ questionable tactics. As the documentary explains, most of the guests came from small towns in what producers called the “Springer Triangle,” which cuts through Tennessee, Ohio and Georgia. Producers lured guests with assurances that going on the show would help them solve their problems, then gave them limo rides and drink tickets to keep the party going the night before taping. Backstage, producers rehearsed with, yelled at and otherwise provoked their guests, all in an effort to make things as combustible as possible.

The show was an inadvertent positive for queer people. As Springer argues in a TV interview excerpted in the documentary, “In a free society, the media should reflect all elements of that society, not just the mainstream.” Unfortunately, Springer’s guests from outside that mainstream were rarely treated with dignity. That was certainly true of gay guests. (Their presence was hardly “a public service thing,” as Sewell put it.) And the show treated transgender people even worse, Sewell noted, focused usually on how they had “duped” their lovers. But for many queer people in the 1990s, cringe was better than nothing. Where else on television, especially during daytime, could gay men see other gay men rip their shirts off and make out as part of a love triangle? As flawed as it was, such visibility mattered, right hooks and all.

Source link