Here is the result in plain text:

Getting vaccinated against shingles can reduce the risk of developing dementia, a large new study finds. The results provide some of the strongest evidence yet that some viral infections can have effects on brain function years later and that preventing them can help stave off cognitive decline. The study, published on Wednesday in the journal Nature, found that people who received the shingles vaccine were 20 percent less likely to develop dementia in the seven years afterward than those who were not vaccinated.

If you’re reducing the risk of dementia by 20 percent, that’s quite important in a public health context, given that we don’t really have much else at the moment that slows down the onset of dementia, said Dr. Paul Harrison, a professor of psychiatry at Oxford. Dr. Harrison was not involved in the new study, but has done other research indicating that shingles vaccines lower dementia risk.

Whether the protection can last beyond seven years can only be determined with further research. But with few currently effective treatments or preventions, Dr. Harrison said, shingles vaccines appear to have “some of the strongest potential protective effects against dementia that we know of that are potentially usable in practice.”

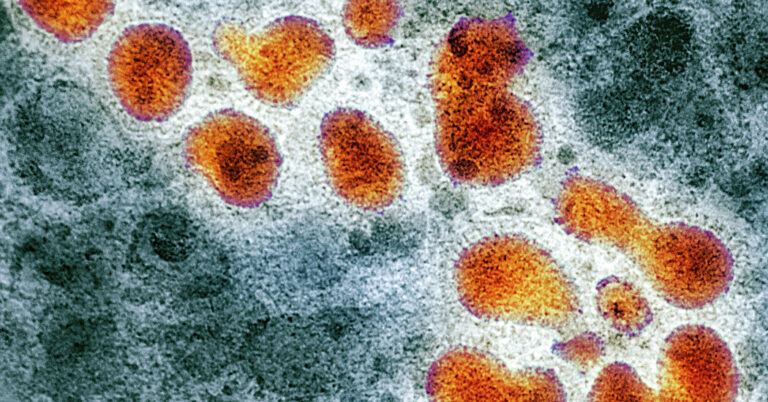

Shingles cases stem from the virus that causes childhood chickenpox, varicella-zoster, which typically remains dormant in nerve cells for decades. As people age and their immune systems weaken, the virus can reactivate and cause shingles, with symptoms like burning, tingling, painful blisters and numbness.

The study emerged from an unusual aspect of a shingles vaccine rollout in Wales on Sept. 1, 2013. Welsh officials established a strict age requirement: people who were 79 on that date were eligible for the vaccine for one year, but those 80 and older, were ineligible. As younger people turned 79, they became eligible for the vaccine for one year.

Researchers tracked health records of about 280,000 people who were age 71 to 88 and without dementia when the rollout began. Over seven years, nearly half of those eligible for the vaccine received it, while only a tiny number from the ineligible group were vaccinated, providing a clear before-and-after distinction.

The study involved an older form of shingles vaccine, Zostavax, which contains a modified version of the live virus. It has since been discontinued in the United States and some other countries because its protection against shingles wanes over time. The new vaccine, Shingrix, which contains an inactivated portion of the virus, is more effective and lasting, research shows.

There are different theories about why shingles vaccines might protect against dementia. One possibility is that by preventing shingles, vaccines reduce the neuroinflammation caused by reactivation of the virus, Dr. Geldsetzer said. Another possibility is that the vaccines rev up the immune system more broadly.

Dr. Maria Nagel, a professor of neurology at University of Colorado School of Medicine, who was not involved in the study, said both theories could be true. There’s evidence for a direct effect as well as an indirect effect, said Dr. Nagel, who has consulted for the manufacturer of Shingrix, GSK.

The study did not distinguish between types of dementia, but other research suggests that the effect of the shingles vaccine for Alzheimer’s disease is much more pronounced than for another dementia.

Source link