Covid vaccines saved lives. Lots of them. Research by the World Health Organization (WHO) now puts the number at 475,000 in the UK with many more kept out of hospital or off a ventilator.

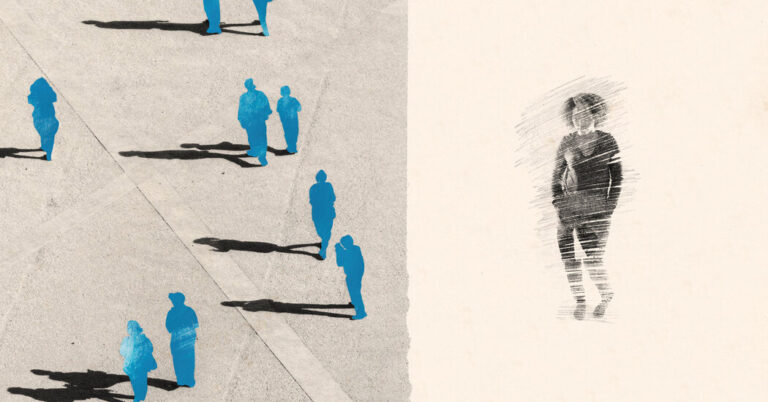

The jabs were a “scientific miracle” we were told at the time, our best hope of life returning to normal after months of lockdown restrictions. But something has happened in the years since. Research suggests confidence in all types of vaccination has taken a significant hit.

“It’s the great paradox of the pandemic,” says Dr Simon Williams, a public health researcher at Swansea University. “One of the most successful innovations in public health history, the rapid development of Covid vaccines, has actually had the effect of reducing public confidence in vaccination.”

In 2023 around 70% of UK adults said that vaccinations were safe and effective, down sharply from 90% in 2018, according to research from the Vaccine Confidence Project, run by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM).

This is very much part of a worldwide trend with 52 of the 55 countries polled seeing a drop in confidence since 2019.

And regular polling carried out by YouGov suggests adults are increasingly likely to say that vaccines have harmful side effects that are not being disclosed to the public. The proportion saying that statement is “probably” or “definitely” true rose to 30% in 2024 from 19% in 2019.

At the same time, childhood vaccination rates have fallen further below recommended levels over the last five years, continuing a longer-term trend.

“Vaccines are always our best defence against infectious, communicable diseases,” adds Dr Williams. “A few percentage drops in the proportion of children covered can make a real difference.”

So why is there increased distrust in vaccination – and can anything be done to change that?

The sudden ‘sea change’ in attitudes

The long-running Covid inquiry has already looked at pandemic planning and the impact on the NHS. This week, though, it opened hearings into the vaccine rollout across the UK, from take-up of the jabs, to their safety, to the way they were marketed to the public.

Dr Helen Wall, a GP from Bolton, saw the shift in vaccines attitudes over the pandemic first-hand.

In May 2021 the town became the centre of national attention; Covid infections more than quadrupled in three weeks driven by the new Delta variant. A huge vaccine drive was ordered with army medics staffing mobile units. Dr Wall led the rollout, as clinical director of the local NHS commissioning board.

“People were coming out and making tea and coffee for people in the line,” she says. “There was this real feeling of camaraderie.”

But since then, Dr Wall has noticed a change in the way people respond to vaccination.

“It’s like they’ve become more tired, jaded and fed-up,” she says. “I think it’s the constant barrage of information, misinformation, and the feeling that they’re being forced into something.”

Figures from NHS England, for example, show the number of frontline healthcare workers getting their flu vaccine fell to 35% in November 2024 from 62% in the same month in 2019.

In late 2021, the government brought in a policy of mandatory Covid vaccines for care home staff in England, and later tried to extend that to NHS workers. At times the public were also told they needed Covid jabs (or a recent negative test) to travel abroad, to enter nightclubs and to visit cinemas in parts of the UK.

Those kinds of strict health policies might force up vaccination rates in the short-term, argues Prof Larson at LSHTM, but there’s a danger we are now starting to pay a “long term price”.

The worry is if people feel forced or coerced into taking a vaccine at certain times, wider vaccine confidence and uptake may experience a backlash.

Personal liberty versus state control

For 200 years vaccination has been entangled with personal liberty, state control and other political issues. That’s increasingly playing out online where the wider debate also takes in global warming, gun control and immigration, for example.

“It’s ‘the people’ versus the political and financial elites, with medical and scientific experts seen as among those deemed elitist, speaking a different language and entwined with big business and pharma,” says Prof Larson.

Meanwhile, President Trump’s controversial pick for US health secretary, Robert Kennedy Jr, has once again put vaccines firmly on the political agenda.

In the past he has repeated the false claim that vaccines cause autism, urged parents not to jab their children, and had to apologise after claiming the number injured by vaccines was “a holocaust”.

He has denied on several occasions that he is anti-vaccination, instead saying he is “pro-safety”.

“We need to be more assertive”

Dr Simon Williams at Swansea University now thinks health authorities have to be clearer about the dangers of some infectious diseases, in the face of online misinformation which often exaggerates the small risk of vaccines.

“Part of the reason tobacco control campaigns have been so effective since the 1980s was because they were so clear about how dangerous smoking is, and I think we can learn from that,” he says.

“We need to be far more assertive about the potential risks of not getting vaccinated.”

Another idea is “pre-bunking” – that is teaching people to expect and recognise misinformation online before they encounter it in real life, instead of relying on fact-checking and dull public health videos after the event.

Prof Heidi Larson also thinks now is the time to target and better engage with those most at-risk of rejecting vaccines – in particular the younger groups that her data shows are most affected.

“I would start in schools, I would start in science classes, I think we are losing the plot if we only focus on disinformation, and don’t start to build an appreciation of how vaccines work and their benefits,” she says.

“Vaccine confidence across Europe is now really struggling and we can’t just assume it’s going to bounce back without a concerted effort.”

Source link