Here is the plain text result:

More than 50,000 spectators filled Kennedy Stadium in Washington on Nov. 27, 1977, for a football game between two bitter rivals, the Washington Redskins and Dallas Cowboys.

There was drama in the game, with both teams in the hunt for a playoff berth, but more unusual was the entertainment before and at halftime: an enormous spectacle of Native American music, dance and history.

At the center of the event was the National Indian Honor Band — 150 students chosen from 80 tribes in 30 states — which played four pieces by Louis W. Ballard. With tens of thousands of listeners, this was probably the most prominent platform a Native American composer had ever had.

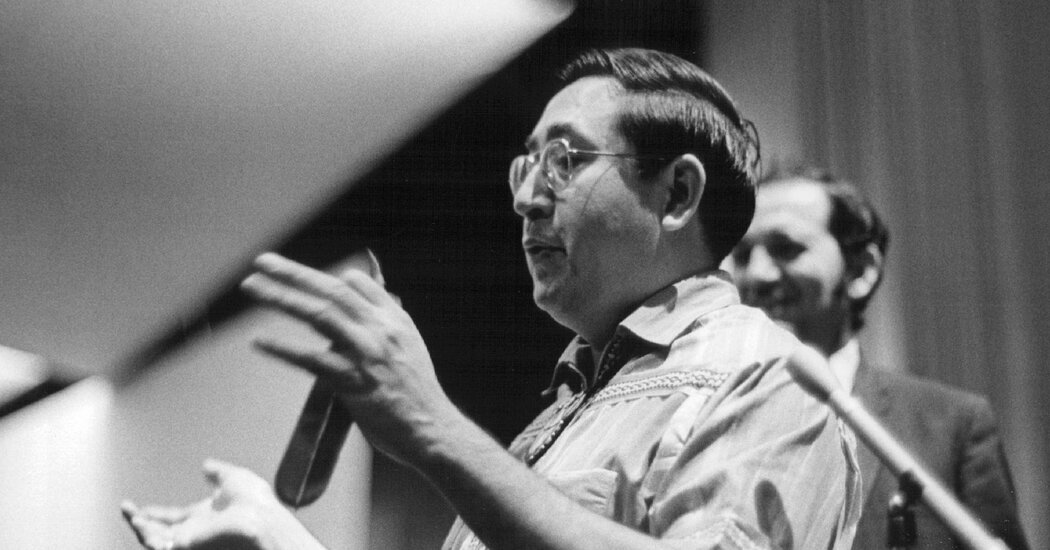

The performance was a career highlight for Ballard, a pioneering figure who paved the way for the broad upswing in Native composers over the past few decades. He was among the first to negotiate issues that younger artists still face: melding Native and Western classical traditions; the role of his music in social and political activism; expressing his community’s deep history and culture in a modern way.

“Ballard was the grandfather of Native American composers,” said Jerod Impichchaaha’a, one of that next generation of artists. “He is the father of all of us who are Native people in classical music right now.”

A composer as well as a pianist, conductor, filmmaker, writer, teacher, compiler of Native songs and national curriculum specialist for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Ballard had his music performed throughout the United States and Europe. He studied with Darius Milhaud and brought Stravinsky to a ceremonial Deer Dance in New Mexico.

But Ballard has not gotten his due. Only a limited amount of his work was commercially recorded, and even less remains in print. When he died of cancer in 2007, at 75, he had no obituary in The New York Times or other major publications. His pieces are infrequently performed.

This is part of the persistent invisibility of Native Americans and their culture. It is telling that CBS was supposed to include that 1977 halftime performance in its national telecast but didn’t. (And yes, today it is eye-rolling that the game was a showdown between the Cowboys and Redskins, who are now the Commanders, after a long battle over their insensitive name.)

In 1960, at the start of his career, Ballard wrote, “Indian music still awaits a rescue from oblivion to take a place in the cultural milieu.” In many ways, that wait continues.

There has been some heartening interest in Ballard, though, particularly since the murder of George Floyd in 2020 turned the attention of many in the cultural world to artists from long-marginalized backgrounds.

Ballard’s family started a website that offers a valuable introduction to his life and music. In 2023, an album on the Naxos label provided a rare hearing for some of his orchestral works. And last summer, at an audience-participation event at Lincoln Center, more people voted for Ballard’s burning 1974 piece “Incident at Wounded Knee” than for Haydn.

The 15-minute “Incident” is a good place to start with Ballard, though it is widely accessible only through an archived video of a 2022 performance by the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, which commissioned it.

The title refers to the 1890 massacre of Native Americans by Army troops at Wounded Knee Creek on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. But the piece was also written in the wake of the two-month occupation of Pine Ridge in 1973, a protest of conditions on the reservation.

In summary, Ballard’s philosophy was to express his creative impulses in a way that his identification as an Indian with a deep cultural heritage and background would enrich his contribution to the musical art.

No biography of Ballard has been published, but there are useful materials around, including a thoroughly researched 2014 dissertation by Karl Erik Ettinger. Ballard was born on July 8, 1931, on the Quapaw reservation in the northeastern corner of Oklahoma. His mother was Quapaw; his father was Cherokee.

His earliest musical experiences came from attending ceremonial powwows with his father and taking music lessons from his mother. When he was 6, he was sent to a government-operated boarding school that was harshly repressive of students expressing Native language or culture. Music ended up a lasting refuge.

“The piano became my surrogate mother and father,” he said. “It was reliable; it was always there.”

He excelled at school through college at the University of Tulsa. After graduating, he found jobs at churches and as a school music teacher. He was making so little money, though, that he started at Tulsa Technical College, planning to become a mechanical draftsman. Miserable, he returned to the University of Tulsa for his master’s degree.

His early works established what would become his standard practice: employing what he called “modified atonality” (distinct from pure Schoenbergian serialism), a strong rhythmic profile, and the combination of instruments from the “two worlds” he inhabited.

“In my music, I have sought to fuse these worlds, for I believe that an artist can get to the heart of a culture through new forms alien to that culture.”

Source link