On Wednesday, the National Transportation Safety Board will convene for three days of hearings into the Jan. 29 midair collision near Ronald Reagan National Airport outside Washington, D.C., that killed 67 people.

The N.T.S.B., an independent government agency that investigates transportation accidents, has already issued its initial findings on the facts and timeline of the episode, in which an Army Black Hawk helicopter crashed into an American Airlines commercial flight above the Potomac River.

The board’s final report, which will identify the cause of the accident, is not expected until next year. But this week’s hearings, which will include sworn testimony from witnesses to the accident and parties to the crash, including the Army, will provide the clearest picture yet of what went wrong.

Here are some of the key questions that have yet to be answered:

Why was the Black Hawk flying too high?

According to the N.T.S.B.’s preliminary report, the pilot flying the Black Hawk, Capt. Rebecca M. Lobach, was told to descend to 200 feet, which was the mandated altitude for helicopters on the route. Yet she evidently had difficulty maintaining that level, putting the Black Hawk in a position where it crashed into the plane at roughly 300 feet.

Was Captain Lobach having trouble controlling the helicopter? Or were her altimeters — instruments that measure altitude — not working properly?

What was the conversation aboard the Black Hawk?

The N.T.S.B. has provided a concise and paraphrased version of what it deems to be key moments from the cockpit voice recordings aboard the Army helicopter, which was carrying a crew of three: Captain Lobach; Chief Warrant Officer 2 Andrew Loyd Eaves, her instructor on the training flight; and Staff Sgt. Ryan Austin O’Hara, the crew chief, or technical expert.

What we don’t know is whether the crew members had any idea how close they were to a catastrophic event, or how concerned they were about either their altitude or a potential problem with their altimeters, which were providing differing readings to Captain Lobach and Mr. Eaves. How concerned did they seem about these factors? Is there any evidence of a last-minute attempt to change altitude or course?

What was going on in the air traffic control tower at National Airport?

Investigators with the N.T.S.B. have found that five air traffic controllers were working various positions at the time of the crash. However, one of the positions had been combined with another to handle both helicopter and airplane traffic hours earlier. The Federal Aviation Administration, which runs the National Airport control tower, has described the staffing that night as “not normal for the time of day and volume of traffic.”

The helicopter position is not typically combined with another position until 9:30 in the evening, people briefed on the practice have told The New York Times, but a supervisor in the tower that night allowed a controller to leave early, prompting the early combination, those people have also said. When, precisely, did that person leave and why? And was the controller who was left performing both positions feeling fatigued or overtaxed by the double duty?

How big of a problem was Runway 33?

While the American Airlines flight was in its final stretch, the control tower asked its pilots to pivot their course from Runway 1, National Airport’s most commonly used arrivals runway, to an alternative, Runway 33. The pilots agreed, putting the airplane on a landing trajectory that risked placing it dangerously close to approaching helicopter traffic.

The N.T.S.B. has said that Runway 33 is used for flight arrivals only 4 percent of the time. Austin Roth, a retired Army Black Hawk instructor pilot who flew those routes many times, said in an interview with The Times that he doubted that the Army crew would have been prepared for a Runway 33 landing, given that runway’s rare use.

Considering all those factors, should the American Airlines crew have refused to land on Runway 33? Was the Black Hawk crew aware of the Runway 33 traffic path it should have been watching? More broadly, why did the F.A.A. allow helicopters to even operate on the route the Black Hawk was flying, when Runway 33 was in use for a landing?

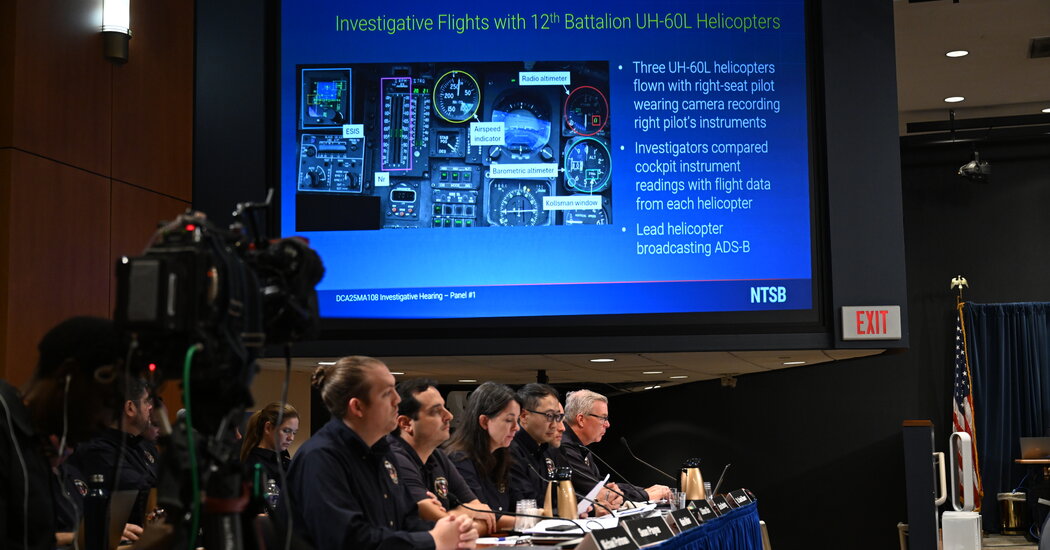

Would a real-time aircraft location broadcasting system have made a difference?

Army officials sought, and received, permission to fly helicopters in the National Airport airspace without using a system known as Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast Out, or ADS-B Out. Concerned lawmakers, including Senator Ted Cruz, the Texas Republican who is the chairman of the Senate’s transportation committee, have flagged the lack of ADS-B as a potentially key contributor to the crash, but the Army has insisted it would not have helped.

Is there evidence suggesting that the system would, in fact, have played a preventive role? An affirmative answer could have broad implications for the Army unit that operates flights in the area in the future.

Source link