Here is the text without any HTML tags or formatting:

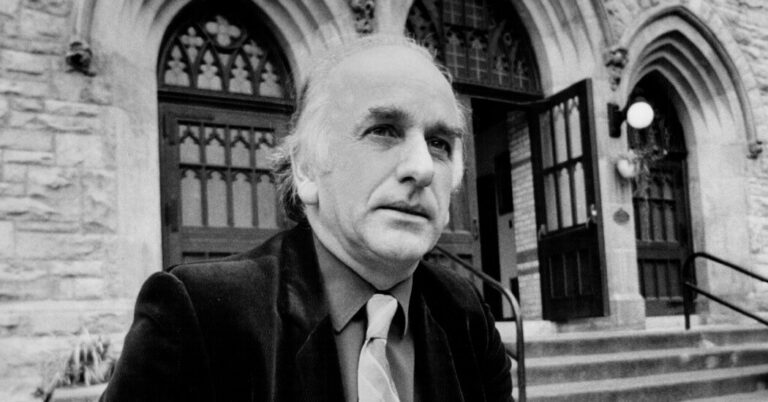

Kilmer S. McCully, a pathologist at Harvard Medical School in the 1960s and ’70s whose colleagues banished him to the basement for insisting – correctly, it turned out – that homocysteine, an amino acid, was being overlooked as a possible risk factor for heart disease, died on Feb. 21 at his home in Winchester, Mass. He was 91.

His daughter, Martha McCully, said the cause was metastatic prostate cancer. His death was not widely reported at the time.

Still a debated idea today, Dr. McCully’s theory – that inadequate intake of certain B vitamins causes high levels of homocysteine in the blood, hardening the arteries with plaque – challenged the cholesterol-focused paradigm backed by the pharmaceutical industry.

Dr. McCully didn’t think cholesterol should be ignored, but he thought it was malpractice to disregard the significance of homocysteine. His bosses at Harvard disagreed. First, they moved his lab below ground; then they told him to leave. He struggled to find work for years.

It was very traumatic, he told the New York Times medical reporter in 1995. People don’t believe you. They think you’re crazy.

Dr. McCully, fashioning himself as a microbe hunter akin to Louis Pasteur, stumbled on homocysteine in the late 1960s at a medical conference in Boston. There, he learned about homocystinuria, a genetic disease in which high amounts of homocysteine are found in the urine of some developmentally disabled children.

How could an eight-year-old have died the way old people do? Dr. McCully wrote, with his daughter, in “The Heart Revolution” (1999).

When Dr. McCully tracked down the autopsy report and tissue samples, he was astounded: the boy had hardened arteries, but there was no cholesterol or fat in the plaque buildup. A few months later, he learned about a baby boy with homocystinuria who had recently died. He also had hardened arteries.

I barely slept for two weeks, he wrote.

In 1969, Dr. McCully published a paper about the cases in The American Journal of Pathology. The next year, in the same journal, he described what happened after he injected rabbits with high doses of homocysteine.

At the end of the day, he was right in the sense that homocysteine is a marker for higher risk for cardiovascular disease, Meir Stampfer, a Harvard epidemiologist who helped lead the study, said in an interview. He gets the credit for developing this theory and helping to provide the evidence for it.

Kilmer Serjus McCully was born on Dec. 23, 1933, in Daykin, Neb., and grew up in Alexandria, Va., near Washington. His father, Harold McCully, was a specialist in counseling psychology for the U.S. Department of Education. His mother, Lulu (Litwinenco) McCully, was an artist and a piano teacher.

As a teenager, Kilmer was enthralled by “Microbe Hunters,” Paul de Kruif’s 1926 book about Pasteur, Walter Reed, Robert Koch and others who investigated infectious diseases. He knew almost immediately that he wanted to become a scientist.

He studied biochemistry, psychology and chemistry at Harvard, where he took classes with B.F. Skinner, and graduated in 1955. Known as Kim to his friends, he went on to earn his medical degree there in 1959. For part-time work, he babysat for the historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. and served cocktails at Mr. Schlesinger’s many parties.

Following an internship and postdoctoral fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital, Dr. McCully joined Harvard Medical School’s pathology department in 1965.

He married Annina Jacobs in 1955. She died in 2023.

In addition to their daughter, Martha, he is survived by their son, Michael; two grandchildren; two great-grandchildren; and a sister, Marilyn McCully.

After the studies in the 1990s supported his theory, Dr. McCully became something of a media star.

The New York Times Magazine featured him in a 1997 article headlined “The Fall and Rise of Kilmer McCully.” On the NPR program “Fresh Air” in 1999, he told Terry Gross, the host, It’s extremely satisfying to me, because when I was a young person, this is what I wanted to do with my life.

But homocysteine remains a controversial subject in medicine.

Major medical organizations have not recommended testing for it, citing mixed results from studies examining whether lowering homocysteine leads to a reduction in cardiovascular events. (There is stronger evidence that it can help prevent strokes.)

It’s a strange business to me that people still don’t pay enough attention to this, Dr. Spence said. Maybe doctors didn’t like their biochemistry lessons.

As for Harvard, Dr. McCully’s family said he was never bitter about his treatment there. At a medical school reunion in 1999, his classmates presented him with a silver platter.

It was inscribed, To Kim McCully, who saw the truth before the rest of us, indeed before the rest of medicine, and who would not be turned aside.

Source link