Here is the plain text result:

The lighting inside The Corner Pub is dim enough that it feels like nighttime even when it’s light outside. There is cheap beer, a wide selection of whiskey and a frozen-drink machine churning “Bushwackers,” described as an adult version of a Wendy’s frosty, full of booze. Sports memorabilia covers the walls — jerseys and photos of famous athletes who have come through over the years, like the late Steve McNair, the city’s first NFL star who used to call the bar’s owner after games to make sure it would stay open for him. A red No. 94 Ohio State jersey hangs over one of the corner tables.

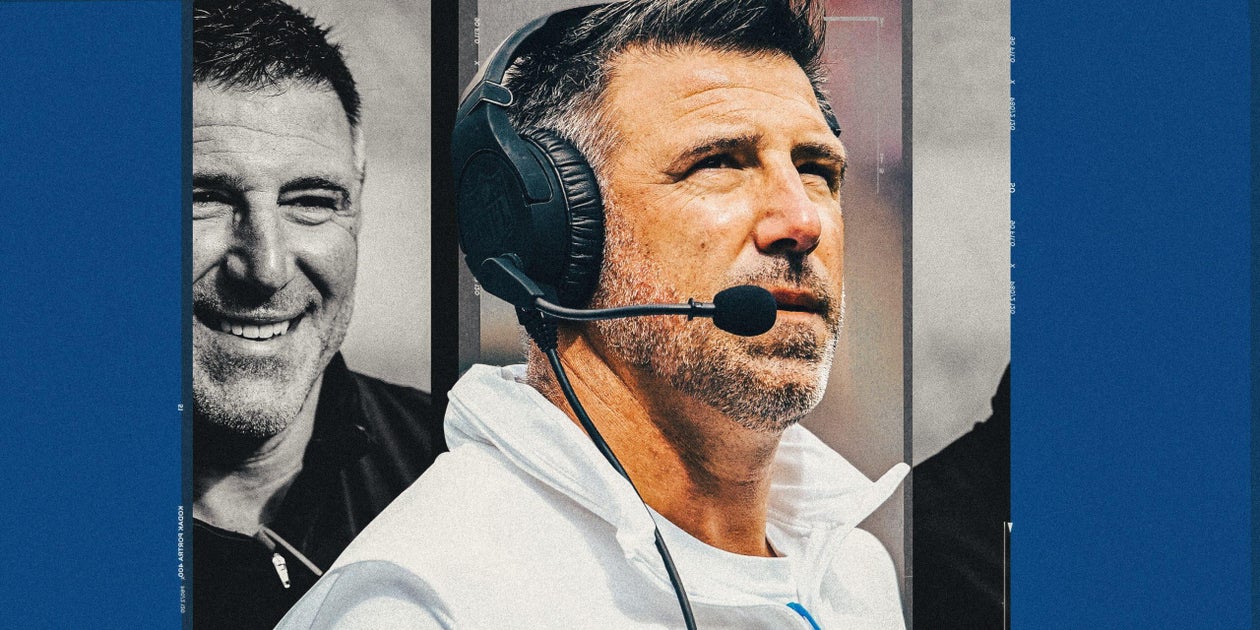

On a Thursday night in August, the pub was packed with regulars and the TVs lining the bar showed an NFL preseason game. After a round of golf, Mike Vrabel took an Uber, walked through the parking lot and came in through the back entrance. He went right to that corner table beneath the Ohio State jersey, his jersey. His golf buddies, whom he met here a couple of years ago, were already waiting for him, light beers in hand.

For the next few hours, Vrabel talked and laughed, and didn’t move from his seat. He remains one of the most recognizable faces in a town known for country music stars (Post Malone was at The Corner Pub the week before). Vrabel is beloved for coaching the Tennessee Titans to the AFC Championship Game in the 2019 season and helping build a winner despite an imperfect roster. But on this night, The Corner Pub’s patrons mostly left him alone, giving him space to enjoy beers and meatballs — the pub is known for those — with his buddies. Aside from a chat with the bar’s owner and his son, only one other person, stumbling, approached Vrabel, simply to let him know the Titans made a mistake firing him months earlier. Vrabel smiled and thanked him.

“I was born for bars like this,” he said later.

For Vrabel, this was a day off from his consulting job with the Cleveland Browns, an endeavor he took after he didn’t land another head-coaching job. Five months later, he is the most coveted candidate of this hiring cycle.

A flurry of interviews awaits, but Vrabel spent this week at his home in Park City, Utah, celebrating the New Year with his family, watching college football and remaining unbothered by the stress of what’s next. The Browns permitted Vrabel to leave with one game left in the regular season, giving him a head start on interviews with teams that already have job openings: The Jets, Saints and Bears, with others soon to come when the regular season ends.

Over the last five months, The Athletic spent extensive time with Vrabel as he worked for the Browns, and worked to create a vision for what his next head-coaching job would look like. He reflected on his time with the Titans, particularly the day it ended, and sized up what he believes is an inaccurate perception many around the league hold of him: a hard-ass, and hard to work with. It’s a challenge to overcome, though it won’t change Vrabel.

“I do love what I heard one time,” Vrabel said: “What somebody thinks of me is none of my business.”

Vrabel was on a break from his duties with the Browns, returning to Nashville for a few days to finalize the sale of his home — he and his wife, Jen, downsized but stayed in town — and, of course, to golf. His phone buzzed throughout breakfast, calls from contractors and inspectors and also Browns colleagues, including tight ends coach Tommy Rees.

Along the way, he shook hands with a few people dining at the restaurant, locals he’s gotten to know over six years in Tennessee. He rested his arms on the back of the booth, took a breath, and told a story about how he recently met a fan who didn’t realize he’d been fired and asked Vrabel how the team was going to be in 2024.

His response was playful but dry: “I couldn’t give two s—s.”

Vrabel was called into Titans owner Amy Adams Strunk’s office on Tuesday, Jan. 9, last year. Team president Burke Nihill was there too. The late-morning meeting was brief, lasting maybe two minutes — Vrabel didn’t have any interest in lingering. He was fired. He asked Strunk to give him an hour to clear out his desk and to address his staff; the owner gave him the OK.

Vrabel gathered more than 20 coaches, the group cramming into a small room at the Titans’ facility. One by one, holding back tears, he told each person how much they meant to him. He told tight ends coach Tony Dews he wished Dews’ four daughters could have finished up their school in one spot. He told defensive coordinator Shane Bowen how much he was going to miss his family, and thanked him for all he’d done for the defense. He told defensive line coach Terrell Williams he was hoping to see Williams’ son graduate from high school and to attend more of his hockey games, and he thanked him for teaching Vrabel how to better connect with his players.

“He had a story for everyone,” Williams said.

“It was off-script and from the heart,” said John Streicher, the team’s director of football administration. “He took a hard day for himself and for everyone else and made everyone feel comfortable and loved, like everything was gonna be OK.”

Vrabel called it “pure instinct.”

Vrabel has spent the past year really considering what he wants out of his next head-coaching job, the kind of coach he wants to be, and what he wants out of the organization that hires him. His season away helped to crystalize his priorities. As always, he broke it down into three keys: Ownership, collaboration, quarterback.

There’s got to be clear communication with ownership, so that we understand as coaches what the expectations are. That’s so we can explain to them what’s reasonable, what we can do, what we probably can do and what we’re going to try to do — or die trying. I want to have a structure in place that people see the game the same way I do from an X’s and O’s standpoint, from a personnel standpoint, with team-building. We would hopefully have that alignment, which is critical.

And I would like to be able to say that there’s a quarterback that you feel like you can win with — or that there’s a path to find the one that you can win with.

In late October, Vrabel took his seat in a crowded New York City restaurant, in town to meet up with some NFL friends. He leaned back into the booth to take up less space at an already-cramped table. He indulged in pasta as wandering eyes began to stare. A man in a Jets hat, dining with his girlfriend, drank a glass of wine and, eventually, mustered up the courage to slide across the booth, putting him by Vrabel’s side.

He asked for a photo; Vrabel obliged.

“Where are you gonna go next?” the man asked. “You gonna come to the Jets?”

Vrabel smiled.

“We’ll see in January.”

Brent Keally and Kent McMillin are regulars at The Corner Pub. In 2019, Vrabel and Jen had stopped in to watch March Madness games. Keally had a table reserved (in the corner, of course) and spotted the coach looking for somewhere to sit in the crowded bar. Keally offered the Vrabels a seat; the group became fast friends.

Everybody else sees him as a guy who blows off people at press conferences,” McMillin said. “But that’s not Mike. Mike is closely vested. And then when he feels comfortable, he opens up. He keeps that circle tight and small.”

Last January, less than a week after Vrabel had been fired, the trio was back at The Corner Pub. Vrabel was at his table, laughing with his buddies, drinking Miller Lite. His friends were stunned when Vrabel didn’t land a head coaching job last offseason, but they never worried about him, because Vrabel wasn’t worried. It’s January — we’re about to see why.

Source link