It may not have been the tax-evasion trial of the century — the second century, that is — but it was of such gravity that the defendants faced charges of forgery, fiscal fraud and the sham sale of slaves.

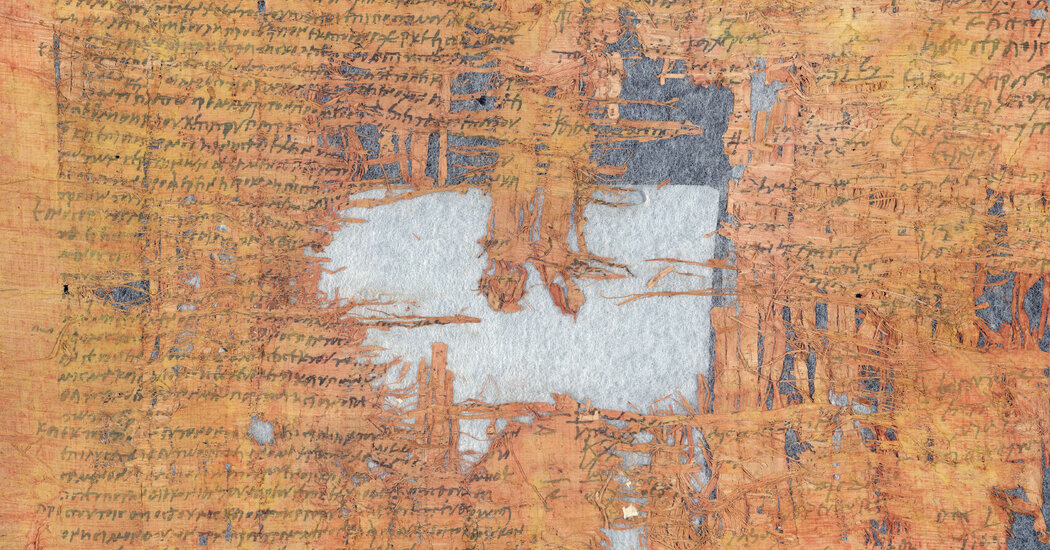

The allegations are laid out in a papyrus that was discovered decades ago in the Judean desert but only recently analyzed; it contains the prosecutor’s prep sheet and the hastily drafted minutes from a judicial hearing.

Both tax dodgers were men. One, named Gadalias, was the impoverished son of a notary with ties to the local administrative elite. Besides convictions for extortion and counterfeiting, his catalog of misdeeds included banditry, sedition and, on four occasions, failing to show up for jury duty at the court of the Roman governor.

Gadalias’s partner in crime was a certain Saulos, his “friend and collaborator” and the supposed mastermind of the caper. Although the ethnicity of the accused is not explicitly stated, their Jewish identities are assumed, based on their biblical names, Gedaliah and Saul.

This ancient legal drama unfolded during the reign of Hadrian, after the emperor’s tour of the area around A.D. 130 and presumably before A.D. 132. That year, Simon bar Kochba, a messianic guerrilla chief, led a popular uprising — the third and final war between the Jewish people and the empire. The revolt was violently suppressed, with hundreds of thousands killed and most of the surviving Jewish population expelled from Judea, which Hadrian renamed Syria Palestina.

The papyrus reflects the suspicion with which the Roman authorities viewed their Jewish subjects. The study of the case offers a window into how Roman institutions and imperial law influenced the administration of justice in a provincial setting where relatively few people were Roman citizens.

The papyrus contains the court proceedings as a case study, which provides rare and highly interesting evidence for the slave trade in this part of the empire, as well as the circumstances under which Jews might have slaves.

The discovery of the papyrus has sparked interest in modern tax lawyers. A German lawyer said the shenanigans of Gadalias and Saulos were not all that different from today’s most common forms of tax fraud — shifting assets, phony transactions.

The case against Gadalias and Saulos was bolstered by information provided by an informant who tipped off the Roman authorities — and the text even suggests that the informant was none other than Saulos, who denounced his accomplice Chaereas to protect himself in a looming financial investigation.

The empire had sophisticated systems for tracking slave ownership and collecting various taxes, which amounted to 4 percent on slave sales and 5 percent on manumissions. The Roman authorities became aware of the tax evasion scheme, and the defendants allegedly made payments to a local city council for protection. The defendants Defence was to blame it on someone else.p

Source link