Here is the result in plain text:

Inside a spacious room on Manhattan’s West Side, rehearsal for the latest Broadway revival of David Mamet’s “Glengarry Glen Ross” was full of macho bluster and trash talk. And that was before the actors started running their scene.

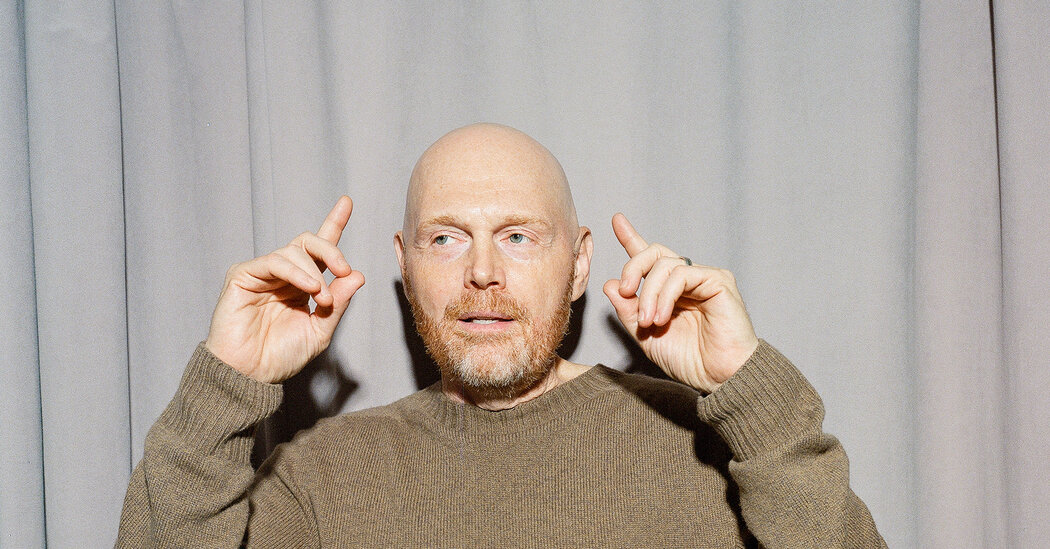

It was a Friday morning, and the show’s British director, Patrick Marber, back after being briefly out sick, approached two of his stars, Bill Burr and Michael McKean. They were sitting inside a makeshift restaurant booth, getting ready to play desperate real estate salesmen entertaining the idea of robbing their office.

Burr loves messing with people. There’s a more accurate verb than “messes,” of course, but I’m not going to use it here. It’s so intrinsic to his needling personality that when I asked him minutes before rehearsal why he’s studying French, Burr described a revenge fantasy of sorts: an eventual stand-up set in France meant to irritate Parisians snooty about Americans mangling their language. Only Bill Burr learns French “out of spite.”

Over the next hour, he kept messing with Marber. When the director, who is also a comedian and playwright, asked him to look at how McKean was using a toothpick in the scene, Burr said sarcastically: “I got to pay attention to him? OK. Sorry.”

At one point, Burr clarified that he was ribbing Marber because he is also a comic: “If he was actually a person,” Burr said, “I’d be hurting his feelings.”

With “Glengarry,” Burr, 56, is entering new territory. He’s acted in movies and in shows like “Breaking Bad” (with his “Glengarry” co-star Bob Odenkirk) and “The Mandalorian,” but this is his professional theater debut.

From a certain angle, it seems unlikely. Over decades of prolific stand-up, Burr projected the persona of the loudmouth ranting at the end of the bar. He told me that for a long time, he didn’t think theater was for him, associating it with musicals, which, he said, “aren’t necessarily my vibe.” Seeing Philip Seymour Hoffman and John C. Reilly on Broadway in “True West” changed his mind. “I saw the power of it,” he said of the production that was staged in 2000. “It was like stand-up, feeding off the energy of the crowd.”

Burr owes this job, funnily enough, to Nathan Lane, an actor he has never met and who is not in the production. Lane, however, was originally asked to star as the older salesman Shelley Levene (Odenkirk took the job after Lane left for a TV series), and had told the producer Jeffrey Richards he would do it only if they cast Burr as Moss.

Lane sent Richards and Marber clips of Burr’s performances, including one of him doing stand-up. “Gentlemen,” he wrote, “pay attention to the arena that is full.” They were convinced. (Lane had less success talking Mamet into putting Alec Baldwin’s “coffee’s for closers” speech from the film adaptation into the play.)

Along with being a great actor, Lane explained that Burr just sounds like a Mamet character. “The anger. The simmering rage,” Lane told me in a phone interview. “There’s a danger to him. That fits into the world of Mamet. I could hear him being a little funny and a little scary.”

Inside a quiet Little Italy cafe, I began to tell Burr there was something he often talks about that resonates with me when he cut me off.

“Whores?” he responded, leaning back and chuckling, in a gray hoodie and jeans. No, I responded, I’m not talking about whores, fully appreciating how funny it sounds for a New York Times journalist to say this in an interview.

I wanted to talk about male anger, a longtime theme of his stand-up. Some of Burr’s funniest bits are about how men, so nervous about appearing sensitive or weak that they won’t risk their masculinity by… accused of flashing a Nazi salute, and the day before I saw him at rehearsal, he was trending on X after TMZ posted a clip from his long-running “Monday Morning Podcast” saying billionaires should be “put down like rabid dogs.”

When I tell him that the right-wing media figure Ben Shapiro said he was going “woke,” Burr shot back: “All he knew is if he put ‘woke’ on what I said, he would make more money. I don’t know who he is, but that guy is a jerk-off.”

Mamet has emerged in recent years as the most Trump-friendly playwright produced on Broadway, but Burr sees the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Glengarry Glen Ross” not unlike critics and academics originally did when it opened in the 1980s: as a critique of winner-takes-all, unfettered capitalism.

“What’s funny is a lot of this play I’ve experienced through the rise of streaming services,” said Burr, who lives in Los Angeles. “When I got into this business 30 years ago, a character actor could make a living. Over the last 20 years, it’s become just the movie star, a couple others. One person at the top is eating this succulent thing and the rest of us are eating the peels.”

Burr is at the top of his profession. Lorne Michaels asked him to do the monologue for the first “Saturday Night Live” episode to air after the presidential election in November. But talk to him enough and you discover his memories as a struggling young person remain fresh. You will hear allusions to the “crazy German Irish house” of his childhood, a place that lacked the warmth of his friends’ homes. Or the early days in comedy when he felt out of his depth.

The “Glengarry” character he most identifies with is not one of Mamet’s hustling, fast-talking salesmen, but James Lingk, the ineffectual mark, the man getting sold and then apologizing for his own lack of power to make decisions. “I was that guy until I was about 30,” he said, adding that he was socially immature for his age. “How I didn’t end up in the trunk of someone’s car is beyond me.”