Here is the result in plain text:

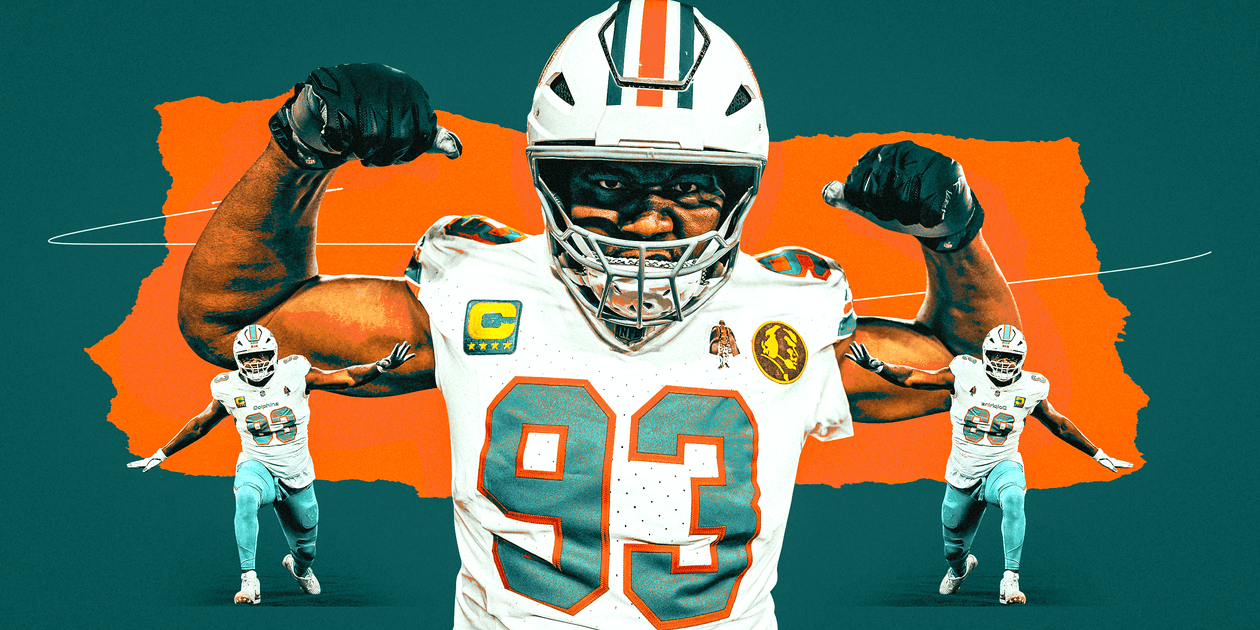

Calais Campbell can still hear his father’s voice. The words were stored away, hardened into his psyche. Charles Campbell saw his son’s path before his son ever could. Twenty years later, the lessons have lasted.

Like the time Calais – long, lean and consumed by football from the minute he first slipped on a helmet – bragged about two first-quarter sacks on the way home from a high school game. He felt on top of the world. Wait until his older brothers heard…

Calais had to wait 50 picks to hear his name called. He’s never forgotten.

“You know how many defensive linemen went ahead of me?” he asks. “Ten.” Most of them didn’t last five seasons. He’s in Year 17.

He’s been playing so long that he once shared a high school field with his head coach.

A month ago, Campbell’s agent called. The trade deadline was nearing. Six teams had reached out to the Dolphins, wanting to deal for the veteran defensive tackle. Among them was the Ravens, where Campbell played from 2020-22. The offer was a fifth-round pick. Another team – Campbell won’t say who – offered a fourth as long as a late-rounder was going back to them.

“Cheap?” Campbell says, flattered. “I’m 38 years old!”

But the Ravens made the most sense. Campbell was going to get another shot at a ring – maybe his last shot. The trade was all but agreed to. Then his phone buzzed.

“I can’t do it,” McDaniel told him. “You’re too valuable to us.” The Dolphins coach had nixed the deal. Campbell would stay.

At that point, the season looked lost. A gilded career would sputter to a forgettable finish.

A few nights later, standing on the sideline before kickoff of a “Monday Night Football” game against the Rams, Campbell heard his father speak to him.

“Once you start something…”

“That’s when I decided I was gonna do everything in my power to get this thing going,” he says./

…Miami is 4-1 since.

One of his favorite teammates, Dolphins tight end Jonnu Smith, calls him the LeBron James of the NFL.

“Always the same old Calais,” Smith says. “Always motivated, always trying to help us.”

Defensive end Zach Sieler admits there’s a running joke inside the position room: with Campbell on the roster, the unit’s average age is 33; without him, it’s 27. “I’m so grateful I get to come to work every day with that guy,” Sieler says. “I’m always asking him, ‘What’s the secret? How are you still doing this?’

Campbell never wanted to do anything else. He’s bounced from Arizona to Jacksonville to Baltimore to Atlanta to Miami. He’s played every position along the defensive line.

“He’ll do anything,” says one of his former coaches, Bruce Arians. “He’s more than just a run-stopper. He’s so rushable. He’ll blow up plays in the backfield. And the best thing he does is use those long arms to bat balls down and tip passes. We got so many interceptions off that.”

Campbell’s missed fewer games (15) than seasons played (17). He’s one of four defensive linemen in league history to make 250 career starts. He’s south of Father Time, but he’s been reared on it, reared himself.

He was 10 years into his career but started to feel like he was in his 20s again.

“I might just do this until the wheels fall off,” he told himself.

He was still writing plays, still studying opponents, still pushing his body to new heights. His father’s words echoed in his mind: “Once you start something…”

He’s thinking.

He’s grown up one of eight, too busy trying to keep up with his older brothers to notice the hard times sneaking up on them. At one point, when Calais was in junior high, the family was forced to spend six months in a homeless shelter, crammed into a room with metal bunk beds pushed against the wall. The boys would take multiple city buses just to get to school each morning.

For years Campbell bottled up the experience, never mentioning it in interviews. He wanted to keep the pain private. But it was always there, same as the words his father left him.

Liver cancer stole Charles Campbell away at age 61, five months before Calais’ high school graduation. His father never saw him suit up at the U. Never saw him play a down in the NFL.

“To tell you the truth, I don’t think my career’s the same without everything I’ve been through,” Campbell says. “We’re all a product of our environment, right? I know I am. I had an incredible father who saw something in me. He pushed me, he motivated me, and all those situations helped build up this callus, this toughness in me. He’s still pushing me.

“That’s such an important part of my story.”

The story since: 17 NFL seasons, six Pro Bowls, a spot on the 2010s All-Decade team and the 2019 Walter Payton Man of the Year award. The foundation Campbell was honored for, the one he started way back in 2013, is called CRC. It’s named after Charles Campbell, whose son is now one of the most revered players in the sport.

But it was late November. Campbell is reflecting on his early beginnings, on the struggles and the triumphs. He’s sitting in his chair, letting the silence linger for a few moments.

He’s a mountain of a man, with the voice of a preacher and a smile that warms the room.

Source link