Longevity in show business is a tricky milestone. For Indian superstar Rajinikanth, 50 years in films isn’t just about survival – it’s about an unbroken reign, turning cinemas into temples and audiences into devotees. Most of his work has been in the thriving Tamil-language film industry, where his films have defined generations.

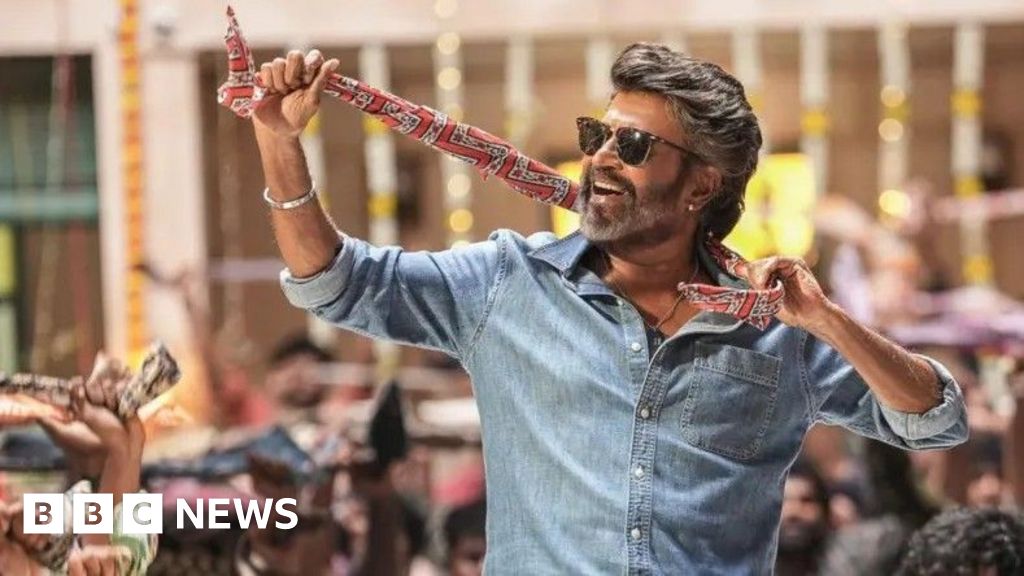

In 1975, a young Shivaji Rao Gaekwad – soon to be known to the world as Rajinikanth – walked on to a Madras (now Chennai) film set for Apoorva Raagangal, debuting in a brief but memorable role as a swaggering rake. Nearly five decades and 170 films on, Rajinikanth’s new film, Coolie, released on 14 August. It celebrates his journey with a story that, in parts, mirrors his own life. He plays a working-class hero taking on a wealthy, oppressive villain.

The 74-year-old superstar is a phenomenon – worshipped in temples built for him, his image carried on airplanes during film promotions, and adored in distant Japan with the passion usually reserved for local idols. Rajinikanth’s story is that of an outsider who became Indian cinema’s most beloved insider – a working-class hero whose appeal cuts across language, class, and geography. His life is an extraordinary rags-to-riches journey – from crippling poverty to unmatched superstardom – earning him the Dadasaheb Phalke Award, India’s highest cinematic honour, and the Padma Vibhushan, the second-highest civilian award.

For millions of fans and some 50,000 fan clubs, this anniversary is another occasion to celebrate their hero. To them, he is a demigod, his idolisation of mythical proportions. “Gods have to appear in somebody’s form,” says A Rajendran, an ardent fan. “Rajinikanth has the power that makes us look up at him.”

Naman Ramachandran, author of Rajinikanth: A Definitive Biography, notes that Rajinikanth’s fans range from Wall Street bankers to washerwomen in Tamil Nadu. His on-screen magic lies in portraying the underdog’s dream: to beat the odds without losing one’s humanity, writes Ramachandran. A 2015 documentary on the superstar called For the Love of a Man by Rinku Kalsy and Joyojeet Pal captured the depth of this fervour – of fans mortgaging homes, selling family gold, and treating film releases as once-in-a-lifetime festivals.

“This isn’t fandom,” Kalsy explained, “it’s identity. He represents what they aspire to be – humble, moral, yet powerful when it matters.” His home in Chennai has become a shrine for thousands of fans seeking a glimpse, a blessing, or the naming of a newborn. In 2016, AirAsia airline unveiled an aircraft emblazoned with his face to mark his film, Kabali’s release; a symbol that his image could carry a film across the skies.

Devotion often spills into social work by his fan clubs organising blood donation camps, relief drives, community events in his name. As Aishwarya Rajinikanth writes in her book Standing on an Apple Box: “My father never ever behaves like a superstar at home… except in his movies.” Rajinikanth’s fan culture also blurs cinema and life. Each film release becomes a ritualised spectacle. As a rookie reporter, I often witnessed the frenzied brotherhood at first day, first-show screenings: coins tossed at the screen, camphor burnt, flowers showered, cut-outs doused in milk, fans screaming his name.

Watching a Rajinikanth movie is less a screening than a carnival that is a heady mix of street cred, working-class pride, communal revelry and delirious joy. After three hours of superhuman justice, humour, romance, and vengeance, cinemas are littered with popcorn like confetti, and fans spill into the streets, whooping with cathartic delight. This year, celebrations have reached fever pitch: in Madurai district, a fan has built a temple adorned with over 5,500 posters and photos, offering prayers to an idol of the star.

One of four children, Rajinikanth grew up in poverty; his father was a police constable. “When I dropped out of college, my father sent me to work as a coolie [porter],” he recalled. A relative later helped him become a bus conductor. A friend, noticing his passion for theatre, pooled funds to send him to the Madras Film Institute, a state-run film school. At the institute, he was talent spotted by the Tamil filmmaker K Balachander who gave him his first role in 1975.

Rajinikanth stood apart from the fair-skinned, soft-spoken hero archetype of Tamil cinema legends like MG Ramachandran. His dark complexion, rustic drawl and streetwise swagger became integral to his cinematic identity. Part of Rajinikanth’s enduring appeal lies in his choice of stories and the range of roles he has played. He began with anti-heroes and villainous roles that won acclaim in films like Apoorva Raagangal, Moondru Mudichu and Pathinaru Vayathinile, and took on morally complex characters in Avargal, Johnny, Mullum Malarum, as well as tragic roles in Bhuvana Oru Kelvikuri.

With the 1980 blockbuster Billa, Rajinikanth cemented his status as an action hero. He went on to star in hit Tamil films, popular Bollywood films, and even a cameo in the American film Bloodstone. From the 1990s, he became known for larger-than-life vigilante roles and portrayals of spiritual figures like Sri Raghavendrar and Baba. In 1998, Muthu unexpectedly became a sensation in Japan. Films like Sivaji and Enthiran, where he played a robot, were massive blockbusters, and despite health challenges, his films continued to achieve huge commercial success.

Critics once dismissed Rajinikanth as a mere “Style King,” known for his cigarette flicks, sunglass twirls, and punchy dialogues laced with wry humour. Yet the values his characters embody – loyalty, courage, humour, and justice – are timeless and universal. Filmmaker SP Muthuraman, who worked with him in 25 films, attributes his success to “hard work, dedication, goodwill, and responsible behaviour towards co-stars, producers, and distributors”.

In Tamil Nadu, where many of his film peers have entered politics, Rajinikanth dabbled in the arena but has never launched a party or contested elections. He thus occupies a unique space – never fully a politician, yet always a moral beacon for his fans. Film historian Theodore Baskaran says that Tamil cinema’s greatest stars occupy a space once held by folk deities. More than a celebrity, Rajinikanth’s influence shapes the devotion of fans who line up at dawn with milk and garlands. They believe that their swashbuckling hero can add colour to their dreams and magic to their lives.

Source link