Here is the plain text result:

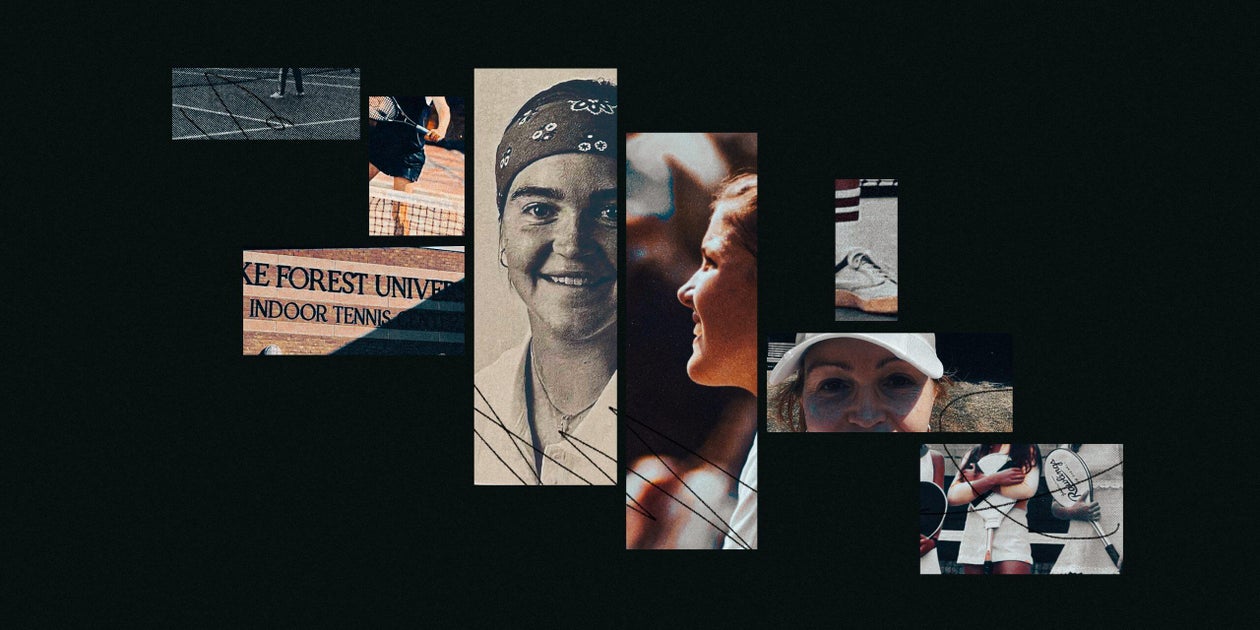

Say nothing. That’s what Caroline Ullring kept telling herself through the final days of March 1999. She had accused her college tennis coach of sexually assaulting her in a Texas motel room during a spring break trip with the team. In late March, she had told athletic department officials about it, including a counselor and the senior women’s administrator, who briefed the athletic director about the allegations. The message Ullring felt she was getting from officials at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, was that it would be best to keep this quiet.

The coach, Lew Gerrard, told the same officials what he told The Athletic earlier this year. He admitted to drinking in the presence of the team, perhaps touching Ullring’s thigh and giving players massages. Nothing else. He agreed to resign. He denied assaulting Ullring.

For the next 20 years, that’s largely what she did. A teammate who heard rumors about the reasons behind Gerrard’s departure asked Ullring about them shortly after he resigned. She said she couldn’t talk about it. She didn’t share details of the alleged assault with her parents or her friends. In 2006, after her boyfriend died suddenly, Ullring was hospitalized, and received treatment from psychologists and psychiatrists. But she hardly discussed the incident with Gerrard, so doctors didn’t diagnose her with post-traumatic stress disorder.

The stories that Ullring and Clark say they have lived with for decades are all too common in sports, especially individual ones like tennis. Young players spend long hours training and traveling with older, mostly male coaches. Too many of those coaches use their power to try to take advantage of those players sexually, sometimes resulting in incidents and relationships that range from inappropriate to criminal.

Clark has lived a lot since then. She had a career in business, working at McDonnell Douglas in Alabama as a buyer for Space Lab parts and as a liaison between purchasing and engineering. She coached collegiate tennis. She married, had children, and became a grandmother. She told no one about the alleged incident with Gerrard until 2006. She was nearly 50 years old, a mother of three, married to her husband, Raoul, for 24 years.

That night, she told her husband about what she remembered happening to her at the Boar’s Head Inn in 1973, though without much detail. She didn’t talk about it again until she entered therapy in 2015. Raoul Clark confirmed the 2006 conversation, and a later one in 2015, when Clark detailed the alleged assault.

Eventually, she told her kids and her friends. Then, in 2019 she tracked down Gerrard and wrote him a letter. She told him not to respond and to never contact her.

In early May, Clark learned that when confronted with her story, Gerrard claimed not to remember her, even though he had coached her for nearly a year.

Clark never stopped thinking about that student at Wake Forest. She wondered if she had struggled alone for years as Clark had. Then, in June 2023, she reached out to Jensen, now a tennis coach at U.C.-Santa Cruz. Could Jensen help her find that student? Days later, Caroline Ullring’s phone lit up.

For 24 years, Ullring had thought her experience with Gerrard was unique. She had thought that somehow she had done something wrong, that it was her fault. In 1999, she had returned to Europe with her secret. She eventually enrolled in medical school in Ireland, but in 2006, in the middle of her studies, her boyfriend died of complications from treatments for a brain tumor. She fell into a deep depression and was admitted for the first of multiple stays in the psychiatric wards of various hospitals. She finished her medical degree, but does not practice medicine.

She underwent electroshock treatments and survived multiple suicide attempts. Working with a psychologist who treated her for post traumatic stress disorder in 2019, she delved into all her traumas. A year ago, though, she was still prone to feelings of ambivalence about living or dying.

Hearing Clark tell her story in a series of messages over text and email, leading up to a video call last summer, changed that. “I wasn’t alone,” she said. “It wasn’t something wrong with me.”

Source link